Getting A Handle On Alcohol

Taken from the Charting Queer Health Episode “Getting A Handle on Alcohol.” Listen to the full interview here.

Whether you’re regretting that last champagne toast from New Years or you’ve been on a sober journey, alcohol has soaked into our culture in almost every area. We drink to celebrate and to mourn; we drink with friends, coworkers, and family. Sometimes, we drink for almost no reason at all. Start out the year by reviewing what we know about alcohol, what it does to you, and how you can improve your own relationship with it.

First, let’s explore the language distinction between alcoholism, alcohol use disorder, and general alcohol use from both a healthcare and cultural perspective. In addiction medicine, language matters due to stigmatization. “Alcohol use disorder” is the preferred term over “alcoholism” or “abuse.” Avoiding moralized language is crucial as alcohol use disorder is considered a disease.

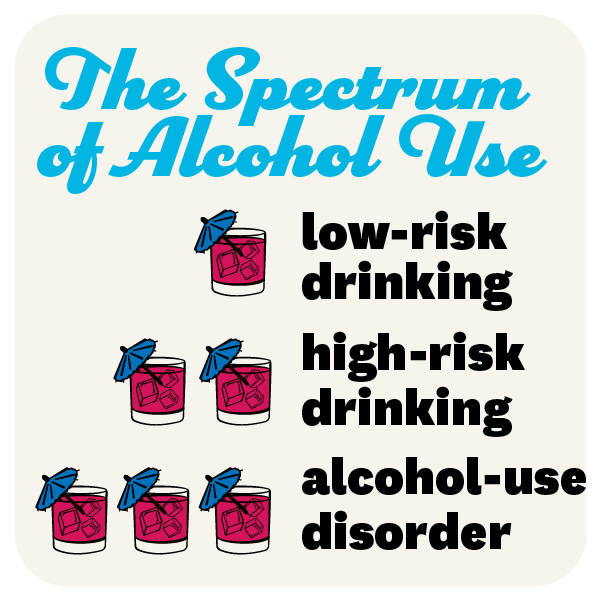

The spectrum of alcohol use includes low-risk drinking, high-risk drinking, and alcohol use disorder. Low-risk drinking is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as two or fewer drinks for men or one or fewer for women in a sitting, with weekly limits. High-risk drinking involves five or more drinks for men or four or more for women in a sitting, or five or more episodes of binge drinking in a month. Alcohol use disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by pathological behaviors related to alcohol.

Circumstances, such as lifestyle and environment, significantly influence alcohol use. The NIAAA’s criteria create a spectrum, recognizing that relationships with alcohol vary. It’s not a black-and-white situation, and the spectrum allows for nuanced assessments and risk stratification. Age and context matter; what may be acceptable for a young adult might not be for an older individual. Society often perceives these scenarios differently, but the key is recognizing the spectrum and understanding the complexities involved.

In discussing alcohol use disorder, the NIAAA doesn’t categorize people by gender but focuses on psychological aspects. I don’t shame my patients; I practice harm-reduction instead, as shame can worsen psychiatric conditions like addiction. The disorder’s diagnosis, based on DSM criteria, doesn’t rely on drink quantity. Genetic factors, family history, adverse childhood experiences, and mental health issues contribute to this diagnosis.

Growing up, we all receive health class lessons full of scare tactics regarding drugs, cigarettes, and alcohol. As adults, there are some real consequences to heavy drinking that we should be mindful of. There are also some ways we can avoid lasting consequences.

The unfortunate truth is that alcohol is poison. There’s no way around that fact, and we shouldn’t lose sight of it. We can, however, be smart about how we use it so we can limit its harmful effects. We all want to keep the fun, the “party” associated with alcohol, so there is a lot of confusion and quite a bit of misinformation regarding it. You may have seen the argument that “Oh, a little bit of red wine is good for you!” Not true. With more research that’s come out recently, we conclude that alcohol is not safe on almost any level, and its toxic effects can be present even in people who only drink in tiny amounts.

WHAT ALCOHOL DOES TO YOU

First off, the more you drink, the more at risk you are going to be for developing various physiologic consequences like depression, anxiety, and more. A lot of people can confirm that waking up the morning after a hazy evening with a phone full of texts can be anxiety-inducing. Other negative health consequences from alcohol can be severe. It has toxic effects on our gastrointestinal tract, not to mention the liver; that’s probably the most well-known organ it affects. It can cause acute liver inflammation, also called hepatitis, or over long periods of time cause fibrosis and scarring of the liver called cirrhosis and liver failure. Alcohol can cause stomach inflammation, otherwise known as gastritis. It affects our cardiovascular system. It can contribute to high blood pressure. It has effects on our our blood. Alcohol can actually have directly toxic effects on the bone marrow and can result in anemia. Not to mention alcohol disrupts sleep and can destabilize mood and exacerbate an underlying mental illness. Alcohol is powerful. It affects every part of our body.

For people who are trying to cut back, I recommend alternating between alcohol and non-alcoholic beverages, starting with a non-alcoholic drink for hydration. Eating before drinking can also be helpful. Counting drinks using apps can provide warnings to avoid overconsumption.

The difficulty arises when practical strategies, though good in theory, become challenging in drinking. Maintaining control over the amount consumed and making sound decisions under the influence of alcohol is… really hard. Things like counting drinks, remembering to drink water, and other strategies are usually not front of mind when you’re drinking. That’s not to mention the challenges alcohol poses to other people, especially as it relates to consent. Let’s say you hook up with someone drunk; you obviously consented at the time, but maybe you wouldn’t have made that decision sober. This kind of murky decision making is a big part of what makes alcohol so problematic.

Ultimately, you should always take responsibility for your actions while drunk. We need to move beyond trivializing alcohol’s effects and laughing off our hangovers, and instead acknowledge the simultaneous cultural ease and difficulty in discussing alcohol, with all its complex and challenging realities.

If you are out in certain queer communities, you may notice that some people try to substitute alcohol for a different substance, like GHB, marijuana, molly, or other things. After all, almost 25% of the general queer community has a moderate alcohol dependency, it follows that we might try to swap it out for something with fewer harmful effects. Unfortunately, I would say that’s not a great idea. Mixing substances, especially something like GHB, can be extremely dangerous, particularly when combined with alcohol. GHB shares a similar mechanism with alcohol, making the mixture especially risky. These substances alter decision-making capacity, and being intoxicated in a setting where people are drinking can escalate into a situation involving multiple substances. It’s a precarious scenario; you don’t want to learn the hard way how substances mix and react.

MEDICATIONS:

There are a variety of medications a doctor can prescribe to help with Alcohol Use Disorder. A medication that’s commonly used is Acamprosate. Acamprosate is thought to work by stabilizing the balance of certain neurotransmitters in the brain, which may be disrupted by chronic alcohol use.

You may have heard of a medication that makes you sick when you drink; that medication is called Disulfuram. It’s primarily used in patients that want to be completely alcohol free and want to take a pill that forces them not to drink because they know if they do, they will get sick; they get physically ill. It’s unpleasant enough to convince a patient not to drink at all. Probably the most commonly used medication is Naltrexone. Naltrexone is an anti-opioid medication, otherwise known as an Opioid Antagonist. It turns out, our brain responds to alcohol like it responds to drugs. So, we can treat them with the same kind of pill that interrupts all the good vibes our brain gets, making alcohol less addictive. You can still drink while taking the medication. It will not block intoxication; it will not make you sick. What it does is it prevents that it interrupts that whole cascade of dopamine-to-endorphins reward system.

These medications, when used as part of a comprehensive treatment plan, can be effective in helping individuals reduce or quit their alcohol consumption. It’s important to note that medication alone is usually not sufficient and combining it with psychotherapy and peer support can enhance treatment outcomes. If someone is considering medication for alcohol use disorder, they should consult with a healthcare professional to determine the most appropriate option based on their individual needs and health history.

Of course, there are programs that exist for someone struggling with alcohol use as well. There are partial hospital programs, otherwise known as IOP programs. These are programs where you go for several hours, multiple times a week. It’s almost like going to school. You’re meeting with counselors, you’re in groups, you’re doing various projects basically to help you enter recovery. This works in tandem with medication, psychotherapy, and peer support.

Recovery with peers is a viable option, the most famous of which is AA or Alcoholics Anonymous. I always hear a lot of rhetoric about AA; there’s a lot of hand waving and arm wringing about it, but AA can be extremely effective and has been for millions of people. There’s also other peer support groups like SMART Recovery or Refuge Recovery. There are also apps! You can talk to people and message with people who are also trying to remain alcohol free or reduce their use. You can even be linked with people who are in the same number of days of sobriety as you, so you could be like, “Oh, we’re on day 10 and, you know, I’m kind of struggling with this!” Then you have a partner in the journey who gets what you’re going through.

I also want to say that recovery is not always just sobriety. I see a lot of patients at Howard Brown who just want to reduce their drinking. They might have an alcohol use disorder even, they may even meet diagnostic criteria, but they’re like, “I’m not ready to completely stop. But I want to reduce my drinking.” There are medications and methods in psychotherapy to help people reduce the amount of that they’re drinking that are highly effective.

Here at Howard Brown, we have a pretty robust network of primary care. So, if patients feel like they’re struggling with alcohol use, they should talk to their doctor or provider about it. I’ve had other providers at Howard Brown reach out to me for their patients as well; it’s an extremely collaborative environment amongst the providers. We’ve called hospitals for our patients that have been hospitalized to help them in terms of substance use disorders to see what can be done. We’ve referred people to medically managed withdrawal, also known as detox from Howard Brown. It’s definitely something that can be tackled in-clinic.

For opiate use disorders, we have a program at Howard Bround which includes peer support, which is amazing. Hopefully one day we can expand this program; I want to really expand it to methamphetamine use, and alcohol use, but that has challenges.

Bottom line, if you’re struggling with alcohol use, there are very effective treatments that can really help you. There is a life in recovery. I think for a lot of people, their block is that they can’t imagine a life without alcohol. But there is an extraordinarily rich life for people in recovery from alcohol. My patients who are in long term remission of alcohol use or other substance use tell me that they feel better than they ever have and that they’re happier and they’re having more fun than they’ve ever had. So, recovery is totally possible; if you feel like you need it, just talk to your doctor about it. I also think if you’re somebody that has embarked on the process of being sober or reducing your alcohol consumption, talking about it is huge. I know for a lot of people, seeing friends or acquaintances talking about it has been helpful and freeing for them to start their own journey with sobriety. I think just, just talking about it on any level, regardless of how serious you’re taking it or how successful you’ve been is important to normalize that conversation.

Queer communities are already at increased risk for substance use disorders and mental health conditions; we should normalize this discussion, normalize sober gathering spaces, and offer sobriety resources for anyone that wants them. Together we can take care of our own and allow us all to live our best lives, whether that is with a drink in hand or not.

If you want to learn more or begin your own journey towards recovery, check out the resources below.